Ren Weiyin Essays

Ren Weiyin in the 1940s was perhaps more renowned for his writing than his painting. He had had several books published on drawing and painting technique and written many essays and articles on art and aesthetics. He also was an enthusiastic traveler throughout China, and edited China's foremost travel magazine until the authorities "transferred" him to become a department store salesman. Here are several of his surviving essays.

任微音自述

Autobiography of Ren Weiyin

I was born in 1918 in Kunming, Yunnan Province. I went to the fifth elementary school of Kunming, which had competent teachers and advanced courses. The art teacher taught traditional Chinese painting and in the first class, the teacher painted a fisherman sitting and fishing in a lonely boat. Beside it was the poem of Liu Zongyuan, the famous Chinese poet:

A hundred mountains and no bird

A thousand paths without a footprint

A little boat, a bamboo cloak

An old man fishing in the cold river-snow.

It was the first painting that made a deep impression upon me.

The name of my father was Ren Sichang. My mother died young -- I can hardly remember her face and I cannot recall anything concerning motherhood. It is sad for me. Even now I feel jealous of my own children as they will have both father and mother when they become adults.

My father remarried and we moved to Shanghai. It was not convenient to move to Shanghai from Yunan then, so we went via Hong Kong. My father became sick and died suddenly a few years later. My stepmother soon followed him. I was raised by my uncle. My American aunt was very good to me. She was the one who first discovered my talent in painting and she arranged for teachers from France, Spain and Russia to teach me painting.

I studied in Taichang Middle School which was famous for its academic rigor. When I graduated from middle school, I did not go to high school, but went back to Shanghai and entered Xinhua Art College. It was then that the Mukden Incident was engineered by the Japanese and the calamity of 20th century China began. Upon graduation from Art College, I entered Shanghai MeiZhuan Painting Research Institute for further education. When I was in Art College, famous painters such as Pan Tianshou, Zhu Lezhi and Huang Binhong were my teachers. The head of the Painting Research Institute was Zhu Yizhan, who specialized in oil painting. Shanghai, as a metropolis with concessions, attracted many foreigners and expatriate Chinese. They brought many famous paintings, which afforded me the chance to see many original pieces at various exhibitions and in private parlors. My eyes feasted on these works of art.

With Japanese aggression increasing, the anti-Japanese cry was raised in China. When I graduated from the Institute in 1937, I left Shanghai for labor service in the countryside of Nanchang, Jiangxi province. Soon The Marco Polo Bridge Incident raised the curtain on the Chinese People's War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression. Later the Japanese captured Shanghai. In the rural area of Nanchang, I did a series of paintings, which were popular among the officers of Jiangxi province. The journal had a special issue and a large exhibition was held in Nanchang Qingnianhui, which was my second exhibition (my first was the family exhibition my aunt hosted for me at our home). The first problem I had in this exhibition was a lack of frames. I made frames of straw and the effect was quite special and splendid.

From Nanchang to Shanghai, the Japanese air force bombed, which caused transportation to stall. The house at Qingnianhui was blown up and my paintings destroyed. I was extremely angry and made a huge anti-Japan poster, hanging it on the camp door of Nanchang. A telegram from my uncle telegram arrived, saying they would move to America. He urged me to join them as soon as possible, but since the transportation lines were completely broken, I could not and began a life “in exile.”

I moved to Guilin from Nanchang but soon Guilin was captured by the Japanese. I went to Hankou where I met Zheng Yongzhi, the director of a Chinese film studio. He offered me a job illustrating movie posters. One day, while drawing the poster for Hot Blood and Faithful Heart, I witnessed the China mechanized force in combat. This was the first mechanized force in China. I was so impressed, I quit the film studio job, rushed to Xiangtan in Hunan province, joined the mechanized force and became the military correspondent and editor of the military newspaper. However, I later became sick. My sister didn’t go to America either and was exiled to Kunming. I missed her and my hometown very much, so I retired from the army and went back to Kunming.

Kunming was far from the war front then. Many intellectuals were there since National Southwest Associated University and National Art College were both moved to Kunming. I had many friends there, such as Lo Lung-chi, Wen Yiduo, Yao Peng Zi, Shu Sheyu, as well as poets Lei Shiyu and Mu Mutian. A year later, I became a teacher at Kunhua Normal School, then Luxi Middle School and lecturer at the National Southwest Associated University. Then I had a chance to go to Chongqing. Shortly after retiring from the military, I was recruited and at the same time I had part-time teaching job at the Southwest and National Art College. In Chongqing I also met Zhang Daqian, Wu Yifeng, Xu Beihong, Wu Zuoren, Li Keran, Zheng Junli and Shi Dongshan.

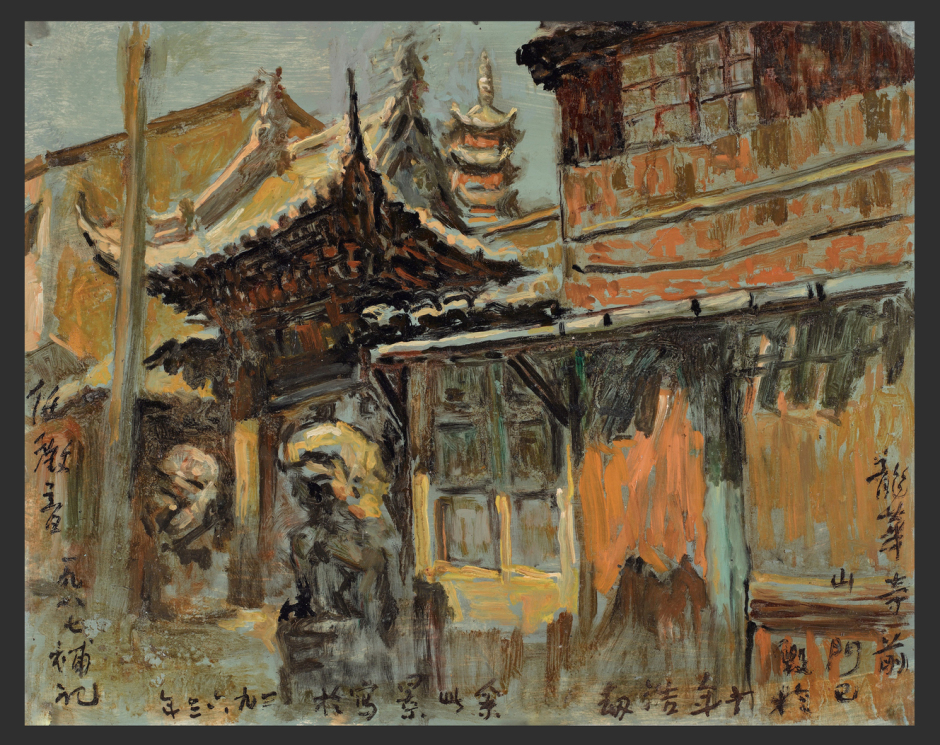

Later, I went to Chengdu and became the principal of Yanting Middle School. It was the autumn of 1943. After being the principal for one year, I came back to Chengdu after the victory of War of Resistance. During the years in Sichuan, I visited Emei, Qingcheng, Dujiangyan and Jianmen, created many paintings and had an exhibition at Wuhan University in Jiading, Sichuan province.

The capital of the national government was moved back to Nanjing, while people exiled to Sichuan were moving back to the east part of China. My uncle came back from America, wrote and asked me again to go to America with him. He also sent an air ticket to Shanghai. But I was married. How could I leave my family and go to a foreign country? My uncle decided I should live in Shanghai temporarily and helped me get a job at The Bank of Shanghai. He returned to America, taking some of my paintings with him.

Soon, I asked to transfer to the affiliated Bank - China travel agency. The travel journal sponsored by the travel agency was the only large-scale travel journal in China. I became the editor. For two years, I travelled and wrote. At that time, travel writing was not popular -- I started the trend. I wrote more than 100 articles on my travels, which were published in various journals and newspapers.

After the liberation of Shanghai, the government, people with “historical problems” could not have a job concerning culture or publicity. I was transferred to Shibai Shopping Mall as a salesman. I was angry and soon quit. I rented a space in the Huaihai Building on Huaihai Road, established a studio and had numerous students. It was perhaps the most advanced art studio in Shanghai. Unexpectedly, however, because of this, I was suspected as a capitalist in early 1960. When Shanghai started the urban collectivization, I finally was labeled and was forced to close the studio in four days and all five family members (with more than 30 pieces of luggage) were relocated to Yinma Farm, Yumen, Gansu province. Many books and documents were destroyed as I could not bring them. The paintings alone -- cut from their frames -- weighed more than 50kg. This was a devastating attack. After reforming for more than a half year, we met severe famine and escaped back to Shanghai.

The lease on my house in Shanghai had expired. I could find nowhere to live, so I had to seek help from the local authorities. They arranged a small apartment on Yanqing Road. I could not have believed then that my family and I would live there for more than twenty years. My past relations and reputation were destroyed. People did not treat me as before. For a living, I did nearly everything, from taking phone calls, to repairing toys to cracking walnuts. Finally, I was made to repair shoes. I did this for 17 years.

During the Culture Revolution, I suffered less numerous attacks, as I had a job. As an “experienced dissident,” though, I had to face “criticism” and “struggle” every year. During those 17 years, though the living conditions were very tough and so many attacks made me even think about death, the art comforted and saved me. I never gave up painting and thinking -- considering the questions of exploring art, to implementing a new practice -- this released me from the disappointments and sufferings of reality. Though all these paintings were done secretly, I had happiness in doing them which created the hope and courage to help me survive. After the Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee (Dec. 1978), I became an employee of the Shanghai Culture and History Institution. The Institution arranged an exhibition for me, which indicated my political rehabilitation. After twenty years of being unrecognized, I finally was afforded civil treatment and some recognition.

Later, I often traveled, painting, participating in all kinds of social activities and trying to make up for lost time. In the spring of 1979, Guangdong Artists Association invited me to have an exhibition in Guangdong province. Also, my work was selected for the first national oil painting exhibition and in the New York Chinese Art Festival.

Then I was invited as the academician of the art gallery of Lijiang Guangxi. Invited by both the Guilin Wen Hua Hotel and Painting and Calligraphy Institute, I exhibited in Guangxi. I went to the second textile factory to do a series of paintings to be exhibited in the factory. Then, I was invited by Shanghai Baosteel to paint the giant mural for their restaurant. Later, I painted a series of paintings for Baosteel and exhibited there. I was the consultant of Baosteel Painting and Calligraphy Society. In 1990, my work representing Shanghai received an award at the Yokohama Friendly Exchange Exhibition.

In 1991, I was invited to the USA as a special painter for the Washington Audio-Visual Center. Just before this, I was invited by the Shanghai

Publicity Department and Art Museum to have an exhibition. The Art Museum collected 14 paintings of mine and published The Collection of Ren Weiyin.

Looking back on my life, most of it was during war and in an unstable society with many misfortunes. When young, I was ambitious about art – but was born in the wrong time and had to endure many difficulties. But I never failed to explore in painting while those setbacks reinforced my confidence. Now, I am specialized in thin oil painting and have hundreds of painting to my credit. I hope my research and work will contribute to the world’s understanding and appreciation of Chinese oil painting.

写于1992年

Incorporating the Techniques and Aesthetic Perspectives of Traditional Chinese and Western Painting Into Modern Chinese Painting

By Ren Weiyin

Modern Chinese painting style draws from all disciplines. Style cannot arise without practice, the Chinese style of oil painting

cannot be pieced together recklessly; it should be naturally formed in practice. We must recognize the advantages of Chinese painting, and though our resources for the study on

Western painting are limited, we should still study the advantages of Western painting, as a way of forging a new path in Oriental painting. Repeated explorations of the various sources

should be used to form our own style, to create a new level, and a new foothold in the world of art.

The tools of oil painting and traditional Chinese painting are different -- the angle, understanding, design, technique -- all are

different. Because of this, innovation and creativity must be based on a full understanding. This essay cites the characteristics of the techniques of Eastern and

Western painting, attempting to make some comparison and explanation on the challenge before us. The observation of [western] oil painters is the intuitive feelings on people and scenes,

somewhat like photography, and the point of their expression is object-oriented.

An artist's job is not to move what they observe to a painting intuitively and unambiguously, but first to take it into their brain, and then

place it into a natural space. Oil painting is a reproduction of "specific" reality, while the traditional Chinese painting is a reproduction of abstract reality. Reproducing a specific

truth, rendering the tiniest nuances, so that apples have flavor, precious stones shine, a baby’s soft skin white under gauze, the power of Napoleon riding his horse into the wind, Dante's

sinking boat and the deathly pallor of those drowned -- so real you almost want to jump into the painting to save them. . . . From a small still life to a huge mural, there are innumerable

expressions of this "reality."

How about traditional Chinese painting? Mountains are on mountains, water on water, buildings on buildings. Close-range vision

is the same as far-range vision. It is very pleasing and, in fact, is another reality. This is so-called "abstract reality," which can also be named “far-observing reality.”

In a painter’s language: it is more resemblance than likeness, more beautiful than beauty, realer than reality, truer than truth.

Western oil painting manifests people with a high degree of realistic techniques. In addition to well-known classical painting schools,

over time, the centers of painting activity changed from that of monks, emperors and aristocrats into the civilian population -- the free consciousness and free feeling of humanity came

into being, and over two centuries, the technique reached its peak. Ancient Chinese painting is also very focused on people, but unfortunately the ancient portraits are mostly made of paper and

silk, and very few are handed down. Now we can see a part of the long scroll "Woman Officer Admonishing Drawing" made by Gu Kaizhi from Dunhuang (stolen by foreign "explorers"), and recently

unearthed ancient tomb paintings, which have also opened our horizons.

Let’s look at the respective advantages in techniques of traditional Chinese painting and western painting. Oil painting renders well

the various colors of sky, dawn, evening mist, the boundless wilderness of field, the sun shining, clouds, landscape and climate, the movement of water -- flowing rivers, gurgling streams, waves

swimming, and swaying reflection. Look at paintings of trees: oil painting depicts trees strongly, from bushes to large forests, from flora next to the small fence to a boundless oasis.

"Trees Under the Wind" by Corot, Shishkin's "Korean Pine Forest," and works by numerous well-known painters make people feel the real presence.

Trees in traditional Chinese painting display another kind of wisdom, featuring temperament and interest arising from the distance and

arrangement of the branches. The wise layout and perfect wielding differs from oil painting which accepts everything of objective existence. Instead, scenes are distinguished

and selected under the principle that beauty comes first. Chinese painters are always cultivated through calligraphy and literature. Inspiration and eccentric imagination occur to

painters as great waves suddenly rushing in the brain. It is characterized by the subjective ideology of scholars with great strength from under the wrist.

In learning Western painting, "the first practice” is “sketch delineation," "observing light and shade" and so on. Then the artist

will have a framework in mind. It results that Western painting has only one point of view of the universe, an unmoved standing point. This is the Western style and the

old painting style.

Whether Chinese paintings are scroll or straight, there is still a picture and a "frame." But when the painter faces the rice paper,

although he paints within the frame, his conception of the universe is infinite and multi-perspective. When he paints, he doesn’t need to consider where the sky is and where the

horizon is, the paper is his playground. The mountains and rivers and other natural scenery are in his brain. The author does not ask from where it comes and where it goes, he

only pays attention to his feelings. Western painting is to be comprehensive, but traditional Chinese painting is to transcend the concentrated expression of the prominent point and go

beyond the

distance and track objects, whilst others are relegated to secondary importance or omitted altogether.

Chinese paintings in flowers, plume, fishes and insects are great achievements and are cherished by collectors from all over the world. In

addition to understanding the mystery of its techniques, we should also glimpse the artist's state of mind when they do their paintings -- a very fundamental factor.

Let’s go further: Oil painting is characterized by the "real", while traditional Chinese painting is characterized by "virtual." Oil

painting must fill all of the canvas and balance all things on it. The painter should be thoughtful and careful. Chinese painting starts from the painter’s mood, using full focus on

things he is interested in, and simplifying or omitting others. Moreover, the master has already figured out how to use the large space on the paper before he paints, which is so-called "having

a well thought out plan,” finishing the painting very quickly. A master of oil painting uses brush stroke as an important part of his expression, but because oil paint is thick and not

free-flowing, he is not able to draw as freely as he wishes. Brushwork also must be looked into when creating a new style of oil painting.

The lines are the most prominent feature of traditional Chinese painting. China's portraiture and the crafts of flowers, birds, fish

and insects are unparalleled in the world; free sketch is also full of irregular lines, the ancient artists created so much in this regard. Western artists Van Gogh, Degas, Matisse

were influenced by the lines’ style, which greatly assisted in the creations of these masters. The "virtual” in Chinese painting is the spirit of the brushwork, it is the source combined with

irregular scattered and exquisitely carved brushwork, which has raised the figure and landscape to an abstract but real height and made a sharp contrast to Western paintings. These

two perspectives are of distant origins, but in modern China, the two perspectives are rising, and converging. While oil painting focuses on the "real," this “reality” is not easy to

learn. Also, the influence of the "virtual" to the West must not be underestimated. In the eighteenth century, the Western impressionist masters gained much inspiration from Chinese

paintings, which led to the revolution of academic painting and their "masters." A deep study of Impressionist development reveals the impact of Oriental painting. First, they raised

their initiative to the first position when observing the character and scenery and became the main objective of the painting. Second, they worked hard to get rid of the "frame" in order to

achieve greater freedom of expression, but unfortunately they did not have the Oriental cosmology, and did not know how to get rid of it.

Though it is very complicated to create a new style of Chinese oil painting, it does not mean there is no viable path. The East takes

the lead on some aesthetic issues and the West takes the lead on others. However difficult, we should dare to think and dare to do, instead of being arrogant and ignorant and looking

backward. I firmly believe that through the efforts of a generation or two, we will be sure to produce great Chinese oil paintings.

Seventeen Years of Shoe Repair

By Ren Weiyin

Shoes have, for centuries, if not millenia, been protecting us, have indeed, been the very foundation upon whichman and woman have stood.

But shoes and shoe repair persons have often been looked down upon. And assuming one is standing or sitting upright this is logical! But how misguided are those who have accorded them

less than their due respect.

I had worked as a shoe repairer for seventeen years, beginning five years earlier [1961] than the Culture Revolution period. At the

beginning, I sat in the shop sadly, wretched and sorrowful, hiding my face towards the wall without courage to raise my head. But as time went by, I gradually felt not so shy, as I thought

repairing shoes should not be such a despicable job. In those years, I was not burdened with so-called business performance and just did my job. As time went on, I acquired more and more

customers and became much busier. Some even called me "old master" to show their goodwill. However, ten years of turmoil opened its curtain. I was once again under siege by the

authorities, and there were limits cast upon me; for example, on numerous holidays when people spent their time joyfully, I had to stay in the shop. But as a shoe repairer, I would be a

law-abiding person whenever I sat before the workbench. So I used an electric iron to spend my eternity. I tried all types of plastic raw materials for any application and made every

effort to renew the old, feeling that I was doing sculpture rather than repairing shoes. In this way, I became more interested in my work, and I formed the habit of long sitting. It was

from my expectation that I really achieved something during long years. In addition to busy tasks, many peers from other districts even came for instructions.

But I could not enjoy any of my humble achievements -- a colleague nicknamed “Old Fox” did everything on behalf of me despite of my covert

resentfulness. Although Old Fox was low in the social ranks, he was an expert in social relations, so he could pick the peaches of others with great social skills. But I wondered: is it a

big thing to me? In the matter of shoe repair, I never wanted to be number 1 in business, so I took it for granted that I received no benefits. At a certain moment, I just thought of

Doctor Manette in “A Tale of Two Cities,” who had repaired shoes over ten years. In some things, my fate was quite similar to his, but there were some differences. . . .

In those days I often was denounced in public. The selected participants were mostly women living around me, each year they shouted out the

slogans against me. In a way, it gave me a strange satisfaction, because I felt I had been forgotten, but that someone remembered to beat me down meant my existence still had value. Even

after I had been put down, some secretly came to comfort me. Once or twice in some years, I secretly walked out to have a look of the Dazibao – big-lettered slogan posters. They made me more

confused, however -- what on earth? there were yet more and more “counter-revolutionists”!? Despite all that, I began feeling that shoe repair is a safe and comforting job. The sense of

safety came from my achievement in the business, as the work got better. The heads would not find trouble with me, while the comfort was that I could find something to balance my discipline,

which was consistent with my art objectives. I came across the idea that any altruistic work, would finally prove to be of benefit to oneself if he shows an honest attitude. I stopped

complaining that there was little time for painting, since I was feeling the bright sunlight, lush plants, and joys during vacations and could see the loveliness of everything in my eyes. They

are the things I could not feel before I encountered my bad fate, and I made some paintings that could not be created by me before or after those days. During that long time, I often thought of

the first words in “Tale of Two Cities”: “It was the best of

times, it was the worst of times; it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness; it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity; it was the season of Light, it was the season

of Darkness; it is the spring of hope, the winter of despair . . . in short . . . very like the present period” -- in China.