Discovering Ren Weiyin -- Outlawed Artist and Shoe Repairman

In Shanghai’s Tian Zi Fang district is an unexpected jewel -- the Ren Weiyin Art Gallery, which exhibits nearly 150 paintings of one of

China’s most important -- and persecuted -- artists of the 20th century. The very existence of Ren’s work is a near-miracle in itself: in 1961 the authorities of “liberated” China

stripped him of his official designation as an artist, making it impossible for his work to be shown, sold, or even discussed, then sent him and his family to a forced labor camp.

Later he was forced to repair shoes -- for 17 years.

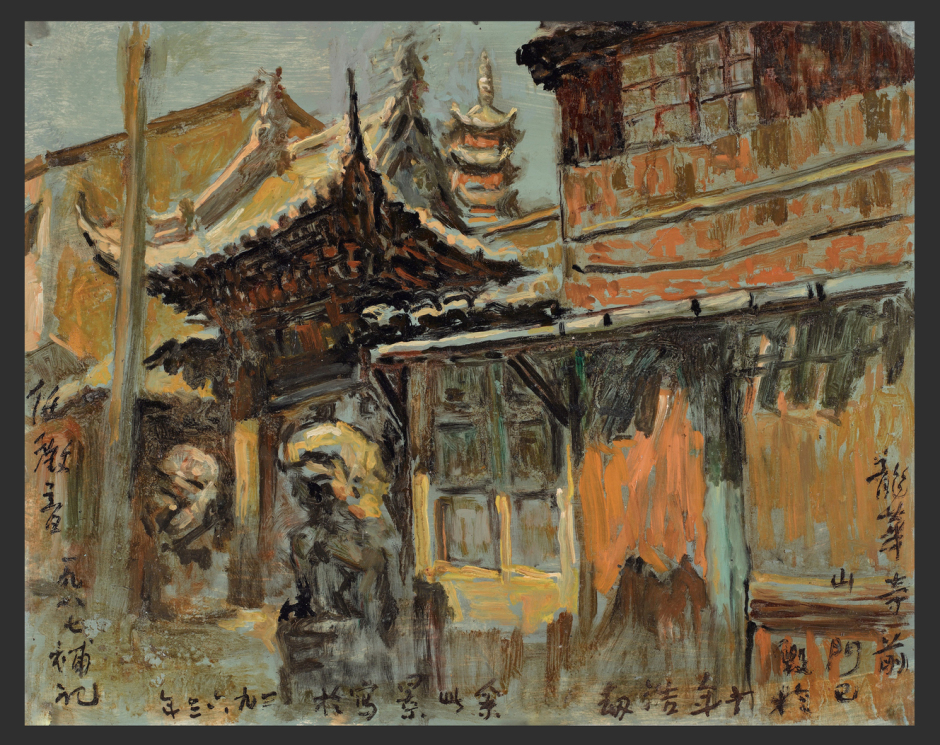

But Ren continued to paint whenever he could, producing hundreds of works. Refusing to follow the predominating kitsch of “socialist realism," he developed his own unique vision and methods. Combining western impressionism with Chinese calligraphic techniques, Ren captured what he called the “vivid human life” of 1950s-70s China with more poetic depth than perhaps any other painter of his time. Though China’s art historians have long recognized this, they have only until recently been able to discuss his work. Consequently, Ren Weiyin is virtually unknown in the west, and not nearly as well-known in China as he deserves. As Chinese art expert Jia Fangzhou noted: “The reappearance of Ren Weiyin should revise the history of Chinese painting. Who can be regarded as similar to him?” The Ren Weiyin Art Gallery and its sumptuous monograph hit the reset button: they provide a splendid -- indeed, revelatory --introduction to a great artist, whose life was nothing short of heroic.

In the mid-1950s, Ren Weiyin was already well known throughout China, having had numerous exhibitions in the major cities, publishing books

on drawing and calligraphic technique, and being China’s foremost travel magazine editor. As the travel writing had been sponsored by a bank, the job was “politically suspect.”

Forced to quit and assigned the job of department store salesman, Ren quit in frustration a few days later and opened his own painting studio in Shanghai, soon known as one of the

best in China, attracting students from all over the country. By night the studio became a symposium for Shanghai’s intellectuals -- professors, artists, writers, students drank tea

and discussed mainly art and philosophy, but carefully avoided politics.

Nonetheless, the security services were highly suspicious. Add that on Friday and Saturday nights the studio hosted ballroom dance

parties until 4 or 5 am to old records of Mantovani or Lester Lanin while the outdoor neon sign, one of only 2 or 3 in all of Shanghai, blinked on and off -- it was all too much.

Shanghai was dark by 8 pm -- few street lights and windows were illuminated. An independent art studio with dancing and a blinking outdoor sign was utterly incompatible with the

revolutionary agenda and in 1961 the studio was forcibly shut down. Ren Weiyin and his family -- wife, son and 2 daughters -- were given 4 days to relocate to Yinma Farm, a notorious

“re-education

through forced labor” camp where many thousands died. They were allowed to bring only what they could carry. The rest of their possessions they sold or gave away. Ren carried

as many of his paintings as possible -- more than 100 kilos of rolled canvasses.

After 9 months of debilitating treatment, living in a cave of bulldozed, compressed earth, the family escaped, following a plan by Ren’s

wife, Jiang Sho-Ching, and returned to Shanghai, living in the cheapest hotels. When discovered by the authorities, they were ordered to return to the forced labor camp. At

this, Jiang Sho-Ching said, “In that case we shall all just die in front of you now and save you the cost of the trip.” The authorities were outraged and embarrassed: “How can you

dare to say such things!” “Because if we return to the camp we will all die anyway, so what’s the difference?” A few days later came the authorities’ decision: the Ren family could

stay in Shanghai, provided they kept their mouths shut about the labor camp. They were assigned a 9 sq.

meter concrete room with no heat, one hanging lightbulb, one small window and a communal kitchen and bath -- their home for 20 years. Ren Weiyin was forbidden to teach, exhibit or sell his

work. His official designation as an artist stripped away meant his work could not even be discussed by academics or critics. Instead, he was forced to be a shoe repairman -- 6 days

a week, for 17 years.

The family, designated as “counter-revolutionaries” and “enemies of the people,” endured abuse, humiliation and deprivation for years.

An Ren, the youngest daughter, recalls a childhood “of constant hunger, dreaming of the time I might be able to eat one entire egg or bun by myself,” and being taken for a walk by her

mother and told she was to be given to another family because theirs had too many mouths to feed. After An begged not to be given away and promising she wouldn’t eat anymore, her

mother relented. It was only through the compassion of friends -- and strangers like those in the marketplaces who, risking censure or worse, would sneak extra portions of food into

the family’s bags -- that the Ren family was able to survive.

Despite all, Ren continued to paint whenever he could get away from the shoe repair stall, mainly using cardboard from discarded laundry soap

boxes. The family supported his efforts, the children often secretly carrying his easel, paints and brushes, following at a distance. Though there was no express sanction

against him painting, it would have invited much “criticism” -- and likely worse -- had the family not taken these precautions; during the Cultural Revolution it would have been near

suicidal. Ren was often publicly denounced and he and the family endured countless insults, sometimes physical. Eventually he took it all philosophically: “That someone remembered

to

beat me down meant my existence still had value.” Ren’s indomitable spirit and dedication and the family’s unconditional support combined for the creation of hundreds of paintings,

many chronicling a Shanghai that has long ceased to exist.

Apart from Ren’s dramatic personal history, however, his paintings demand attention on their own significant merits. The drama of

Ren’s tribulations and our broadened contemporary perspective can obscure the adventure, nerve and rigor of this unique body of work. While much of China’s significant historical art

was being destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, Ren was quietly forging a conduit from the past to the future while assiduously avoiding the Social Realist present.

Informed by French and Russian Impressionism, Ren brought the vivid, broken brushwork, western linear perspective and directly observed

Shanghai subject matter together in a personally meaningful way. Importantly, while pointing the way forward, he honored the calligraphic past and built on the vast ink-and-paper

vocabulary that was his artistic heritage. Additionally, he made ingenious use of the technical strictures imposed upon him. One might say that he thinned his paint to save

precious materials but the fluid, organic results embrace accidents and put them to use as a metaphor for real, unpredictable, teeming, vivid humanity as well as for their inherent abstract

beauty.

Ren often used the underlying color of the cardboard on which he painted to unify and soften his colors, making him more of a tonal brother

to Vuillard than Van Gogh. But then his carefully observed, subtly insinuated light imbues even the most casual of his paintings with a humid freshness and presence that takes one on a tour

not only of the old Shanghai, but also the sensuousness of its seasons.

The people in Ren’s paintings have no political agenda. Rather, and far more meaningfully, they represent real humanity about its business

-- shopping, having a smoke, repairing a bicycle, chatting over tea. The only ideology that can be ascribed to Ren’s work is that it affirms that life goes on despite ideology, that

humanity endures humiliation, deprivation and hardship and yet carries with it no small amount of culture, no matter how persecuted or banned. The combinations of past and present,

conviction and lightness, description and experimentation transcend time, race and nationality and make the paintings of Ren Weiyin refreshingly relevant to the contemporary eye. We’ve

become inured to the garish, shocking and irreverent. It is the very reverence, the quiet but almost ecstatic embrace of the everyday, that elevates Ren’s work to the high position it

occupies.

Now that his work has resurfaced, the intellectual and emotional freedom Ren Weiyin insisted upon in his work is available to all. In

Tian Zi Fang the Ren Weiyin Art Gallery offers an opportunity to experience a glorious record of a time, a city and a man long suppressed but never more relevant than now.

Joe Chonto

Leslie Bell